Surface Wave Climatology

Published in Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 2021

Recommended citation: Colosi, L. V., Villas Bôas, A. B., & Gille, S. T. (2021). The seasonal cycle of significant wave height in the ocean: Local versus remote forcing. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 126, e2021JC017198. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JC017198 https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JC017198

Overview

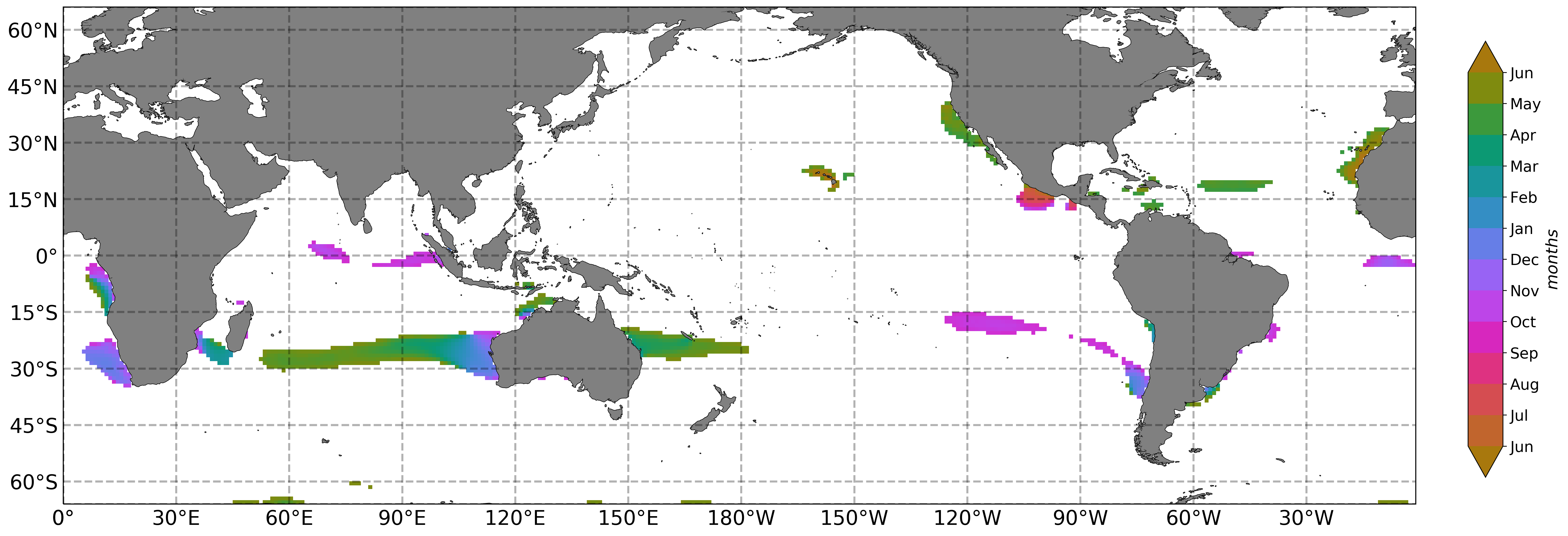

In December 2017, I began working with Professor Sarah T. Gille on a project investigating the intra-annual variability of significant wave height (SWH) in regards to SWH relationship with local wind speed (WSP). Significant wave height (SWH) stems from a combination of locally generated “wind-sea” and remotely generated “swell” waves. In the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, wave heights typically undergo a sinusoidal annual cycle, with larger SWH in winter in response to seasonal changes in high-latitude storm patterns that generate equatorward propagating swell. However, some locations deviate from this hemispheric-scale seasonal pattern in SWH. For example, in the California coastal region, local wind events occur in boreal spring and summer, leading to a wind speed (WSP) annual cycle with a distinct maximum in boreal spring and a corresponding local response in SWH. Here ocean regions with a WSP annual cycle reaching a maximum in late spring, summer, or early fall are designated as seasonal wind anomaly regions (SWARs). Intra-annual variability of surface gravity waves is analyzed globally using two decades of satellite-derived SWH and WSP data. The phasing of the WSP annual cycle is used as a metric to identify SWARs. Global maps of probability of swell based on wave age confirm that during the spring and summer months, locally forced waves are more statistically more likely in SWARs than in surrounding regions. The magnitude of the deviation in the SWH annual cycle is determined by the exposure to swell and characteristics of the wave field within the region. Local winds have a more identifiable impact on Northern Hemisphere SWARs than on Southern Hemisphere SWARs due to the larger seasonality of Northern Hemisphere winds.

Link to Supplementary Material.

Figure 4: Annual cycle phase for CCMP2 wind speed, highlighting SWARs using the WSP maximum criteria. White pixels correspond to points that are not categorized as having anomalous phase or where the amplitude is not statistically significant.